Kleene's recursion theorem

In computability theory, Kleene's recursion theorems are a pair of fundamental results about the application of computable functions to their own descriptions. The theorems were first proved by Stephen Kleene in 1938.

The two recursion theorems can be applied to construct fixed points of certain operations on computable functions, to generate quines, and to construct functions defined via recursive definitions.

Contents |

The second recursion theorem

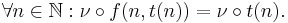

The second recursion theorem is closely related to definitions of computable functions using recursion. Because it is better known than the first recursion theorem, it is sometimes called just the recursion theorem. Its statement refers to the standard Gödel numbering φ of the partial recursive functions, in which the function corresponding to index e is  .

.

- The second recursion theorem. If F is a total computable function then there is an index e such that

.

.

Here  means that, for each n, either both

means that, for each n, either both  and

and  are defined, and their values are equal, or else both are undefined.

are defined, and their values are equal, or else both are undefined.

Example

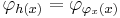

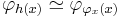

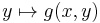

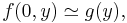

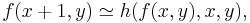

Suppose that g and h are total computable functions that are used in a recursive definition for a function f:

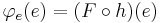

This recursive definition can be converted into a computable function F(e) that takes an index for a program e and returns an index F(e) such that

In this context, a fixed point of F is an index e such that  ; the function computed by such an e will be a solution to the original recursion equations. The recursion theorem establishes the existence of such a fixed point, assuming that F is computable, and is sometimes called (Kleene's) fixed point theorem for this reason. The theorem does not guarantee that e is an index for the smallest fixed point of the recursion equations; this is the role of the first recursion theorem described below.

; the function computed by such an e will be a solution to the original recursion equations. The recursion theorem establishes the existence of such a fixed point, assuming that F is computable, and is sometimes called (Kleene's) fixed point theorem for this reason. The theorem does not guarantee that e is an index for the smallest fixed point of the recursion equations; this is the role of the first recursion theorem described below.

Proof of the second recursion theorem

The proof uses a particular total computable function h, defined as follows. Given a natural number x, h outputs the index of the partial computable function that performs the following computation:

- Given an input y, first attempt to compute

. If that computation returns an output e, then compute

. If that computation returns an output e, then compute  and return its value, if any.

and return its value, if any.

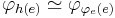

Thus, for all x, if  halts, then

halts, then  , and if

, and if  does not halt then

does not halt then  does not halt; this is denoted

does not halt; this is denoted  . The function h can be constructed from the partial computable function

. The function h can be constructed from the partial computable function  and the s-m-n theorem: for each x,

and the s-m-n theorem: for each x,  is the index of a program which computes the function

is the index of a program which computes the function  .

.

To complete the proof, let F be any total computable function, and construct h as above. Let e be an index of the composition  , which is a total computable function. Then

, which is a total computable function. Then  by the definition of h. But, because e is an index of

by the definition of h. But, because e is an index of  ,

,  , and thus

, and thus  . By the transitivity of

. By the transitivity of  , this means

, this means  . Hence

. Hence  for

for  .

.

Application to quines

One informal interpretation of the second recursion theorem is that any partial computable function can guess an index for itself. This follows from the following corollary of the theorem (Cutland 1980: p. 202).

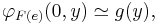

- Corollary. For any partial recursive function Q(x,y) there is an index p such that

.

.

The corollary is proved by letting  be a function that gives an index for

be a function that gives an index for  .

.

The corollary shows that for any computable function Q of two arguments there is a program that takes one argument and evaluates Q with the index of that very program as the first argument and the given argument as the second. Note that this program is able to generate its index from information built in to the program; it does not require any external resources in order to find the index.

A classic example is the function Q(x,y) = x. The corresponding index p in this case yields a computable function that outputs its own index when applied to any value (Cutland 1980: p. 204). When expressed as computer programs, such indices are known as quines.

The following example in Lisp illustrates how the p in the corollary can be effectively produced from the function Q. The function s11 in the code is the function of that name produced by the S-m-n theorem.

; Q can be changed to any two-argument function. (setq Q '(lambda (x y) x)) (setq s11 '(lambda (f x) (list 'lambda '(y) (list f x 'y)))) (setq n (list 'lambda '(x y) (list Q (list s11 'x 'x) 'y))) (setq p (eval (list s11 n n))) ; The results of the following expressions should be the same. ; φ_p(nil) (eval (list p nil)) ; Q(p, nil) (eval (list Q p nil))

Fixed-point free functions

A function F such that  for all e is called fixed point free. The recursion theorem shows that no computable function is fixed point free, but there are many non-computable fixed-point free functions. Arslanov's completeness criterion states that the only recursively enumerable Turing degree that computes a fixed point free function is 0′, the degree of the halting problem.

for all e is called fixed point free. The recursion theorem shows that no computable function is fixed point free, but there are many non-computable fixed-point free functions. Arslanov's completeness criterion states that the only recursively enumerable Turing degree that computes a fixed point free function is 0′, the degree of the halting problem.

The first recursion theorem

The first recursion theorem is related to fixed points determined by enumeration operators, which are a computable analogue of inductive definitions. An enumeration operator is a set of pairs (A,n) where A is a (code for a) finite set of numbers and n is a single natural number. Often, n will be viewed as a code for an ordered pair of natural numbers, particularly when functions are defined via enumeration operators. Enumeration operators are of central importance in the study of enumeration reducibility.

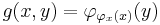

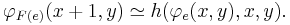

Each enumeration operator Φ determines a function from sets of naturals to sets of naturals given by

A recursive operator is an enumeration operator that, when given the graph of a partial recursive function, always returns the graph of a partial recursive function.

A fixed point of an enumeration operator Φ is a set F such that Φ(F) = F. The first enumeration theorem shows that fixed points can be effectively obtained if the enumeration operator itself is computable.

- First recursion theorem. The following statements hold.

- For any computable enumeration operator Φ there is a recursively enumerable set F such that Φ(F) = F and F is the smallest set with this property.

- For any recursive operator Ψ there is a partial computable function φ such that Ψ(φ) = φ and φ is the smallest partial computable function with this property.

Example

Like the second recursion theorem, the first recursion theorem can be used to obtain functions satisfying systems of recursion equations. To apply the first recursion theorem, the recursion equations must first be recast as a recursive operator.

Consider the recursion equations for the factorial function f:

- f(0) = 1,

- f(n+1) = (n + 1) · f(n).

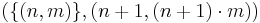

The corresponding recursive operator Φ will have information that tells how to get to the next value of f from the previous value. However, the recursive operator will actually define the graph of f. First, Φ will contain the pair  . This indicates that f(0) is unequivocally 1, and thus the pair (0,1) is in the graph of f.

. This indicates that f(0) is unequivocally 1, and thus the pair (0,1) is in the graph of f.

Next, for each n and m, Φ will contain the pair  . This indicates that, if f(n) is m, then f(n + 1) is (n + 1)m, so that the pair (n + 1, (n + 1)m) is in the graph of f. Unlike the base case f(0) = 1, the recursive operator requires some information about f(n) before it defines a value of f(n + 1).

. This indicates that, if f(n) is m, then f(n + 1) is (n + 1)m, so that the pair (n + 1, (n + 1)m) is in the graph of f. Unlike the base case f(0) = 1, the recursive operator requires some information about f(n) before it defines a value of f(n + 1).

The first recursion theorem (in particular, part 1) states that there is a set F such that Φ(F) = F. The set F will consist entirely of ordered pairs of natural numbers, and will be the graph of the factorial function f, as desired.

The restriction to recursion equations that can be recast as recursive operators ensures that the recursion equations actually define a least fixed point. For example, consider the set of recursion equations:

- g(0) = 1,

- g(n + 1) = 1,

- g(2n) = 0.

There is no function g satisfying these equations, because they imply g(2) = 2 and also imply g(2) = 0. Thus there is no fixed point g satisfying these recursion equations. It is possible to make an enumeration operator corresponding to these equations, but it will not be a recursive operator.

Proof sketch for the first recursion theorem

The proof of part 1 of the first recursion theorem is obtained by iterating the enumeration operator Φ beginning with the empty set. First, a sequence Fk is constructed, for  . Let F0 be the empty set. Proceeding inductively, for each k, let Fk + 1 be

. Let F0 be the empty set. Proceeding inductively, for each k, let Fk + 1 be  . Finally, F is taken to be

. Finally, F is taken to be  . The remainder of the proof consists of a verification that F is recursively enumerable and is the least fixed point of Φ. The sequence Fk used in this proof corresponds to the Kleene chain in the proof of the Kleene fixed-point theorem.

. The remainder of the proof consists of a verification that F is recursively enumerable and is the least fixed point of Φ. The sequence Fk used in this proof corresponds to the Kleene chain in the proof of the Kleene fixed-point theorem.

The second part of the first recursion theorem follows from the first part. The assumption that Φ is a recursive operator is used to show that the fixed point of Φ is the graph of a partial function. The key point is that if the fixed point F is not the graph of a function, then there is some k such that Fk is not the graph of a function.

Comparison to the second recursion theorem

Compared to the second recursion theorem, the first recursion theorem produces a stronger conclusion but only when narrower hypotheses are satisfied. Rogers [1967] uses the term weak recursion theorem for the first recursion theorem and strong recursion theorem for the second recursion theorem.

One difference between the first and second recursion theorems is that the fixed points obtained by the first recursion theorem are guaranteed to be least fixed points, while those obtained from the second recursion theorem may not be least fixed points.

A second difference is that the first recursion theorem only applies to systems of equations that can be recast as recursive operators. This restriction is similar to the restriction to continuous operators in the Kleene fixed-point theorem of order theory. The second recursion theorem can be applied to any total recursive function.

Generalized theorem by A.I. Maltsev

Anatoly Maltsev proved a generalized version of the recursion theorem for any set with a precomplete numbering. A Gödel numbering is a precomplete numbering on the set of computable functions so the generalized theorem yields the Kleene recursion theorem as a special case.

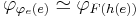

Given a precomplete numbering  then for any partial computable function

then for any partial computable function  with two parameters there exists a total computable function

with two parameters there exists a total computable function  with one parameter such that

with one parameter such that

See also

- Denotational semantics, where another least fixed point theorem is used for the same purpose as the first recursion theorem.

- Fixed-point combinators, which are used in lambda calculus for the same purpose as the first recursion theorem.

References

- Cutland, N.J., Computability: An introduction to recursive function theory, Cambridge University Press, 1980. ISBN 0-521-29465-7

- Kleene, Stephen, "On notation for ordinal numbers," The Journal of Symbolic Logic, 3 (1938), 150–155.

- Rogers, H. The Theory of Recursive Functions and Effective Computability, MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-68052-1; ISBN 0-07-053522-1

External links

- Recursive Functions entry by Piergiorgio Odifreddi in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 2005.

![\Phi(X) = \{ n \mid \exists A \subseteq X [(A,n) \in \Phi]\}.](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/0e636e3d5cbbe2e4e570141544ba3537.png)